Caring for our Future: Addressing Nebraska's Child Care Crisis

Stable, responsive, and consistent care at a young age sets children up for a great early start in life. In a functioning early child care and education system, parents would be able to access quality care at an affordable price, child care providers could operate successful businesses, and child care workers would receive fair compensation enabling them to support their own families. Unfortunately, Nebraska’s early child care and education system is falling short on all these standards. Costs are high and rising, and parents often struggle with waitlists or long commutes to access care. Meanwhile, providers are struggling to cover operating costs and child care workers are poorly compensated and burnt out. Here, in the 31st annual Kids Count in Nebraska Report, we examine some of the challenges facing Nebraska’s early child care and education system in more detail and recommend some policy solutions to ensure every working family in our state has access to safe, quality care they can afford.

Importance of Early Child Care and Education

Early child care and education are foundational to modern economics and communities in two important ways. First, for parents with young children, access to affordable care is required for participation in the economy. Second, quality care and education promotes a child’s cognitive, social, and emotional development, setting the stage for their formal education and, eventually, their future ability to contribute to the economy and their community.

Nowadays, whether due to changing gender norms, stagnating wages, or other societal shifts, more parents are participating in the economy than ever before. In the U.S., employment rates of mothers with children ages 3 to 7 has increased from just below 20% in 1950 to 67% in 2018.i Nebraska’s parents are no different and, in fact, the evidence suggests they are more likely to be working than the U.S. average. Ten years ago, in 2014, 70% of Nebraska’s children under the age of 6 had all available parents in the workforce. In 2022, that percentage has risen to 74%, significantly higher than the national average of 68%.ii In addition, another 6% of parents in Nebraska quit, did not take, or changed their job because of child care problems.iii

With parents at work, children still need consistent, caring, and responsive relationships and educational experiences. Luckily, as the Harvard University Center on the Developing Child explains, decades of research have established that “high-quality caregiving in the early childhood period that is stable and responsive has a greater impact on child outcomes than where that care is provided”.iv The task, then, is to ensure that all children of working parents have such care, rather than the highly variable caregiving networks currently available.

Access

For working parents, child care needs to be close to home or work, accessible by transit, and be available during working hours. Nebraska has long been challenged in these regards, particularly in rural parts of the state.v

Unfortunately, since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, access has become only more difficult. In this respect, Nebraska’s problems are not unique. Nationwide, the number of employed people who missed work due to child care problems doubled in 2020 and remained well above pre-pandemic levels as of 2022 (see Figure 1).vi

In Nebraska, from 2020 to 2022, there was a 17% decline in the number of licensed child care facilities. Figure 2 presents the capacity of licensed child care facilities per 100 children under the age of 6 with all available parents working for each county in Nebraska.vii In this figure, counties with higher scores have higher child care capacity, with a score of 100 representing full capacity to meet the potential need.

As you can see, in 2022, nine counties had zero child care capacity, classifying them as child care deserts (Arthur, Banner, Blaine, Hayes, Keya Paha, Logan, McPherson, Sioux, Thomas). Meanwhile, another 23 counties received scores between 1 and 50, meaning those counties could not meet the licensed child care needs for at least half the county’s young children of an age to require care. At a recent community meeting held in Central Nebraska, Voices for Children staff heard fears that their towns would not survive unless their residents gained better access to child care.

Affordability

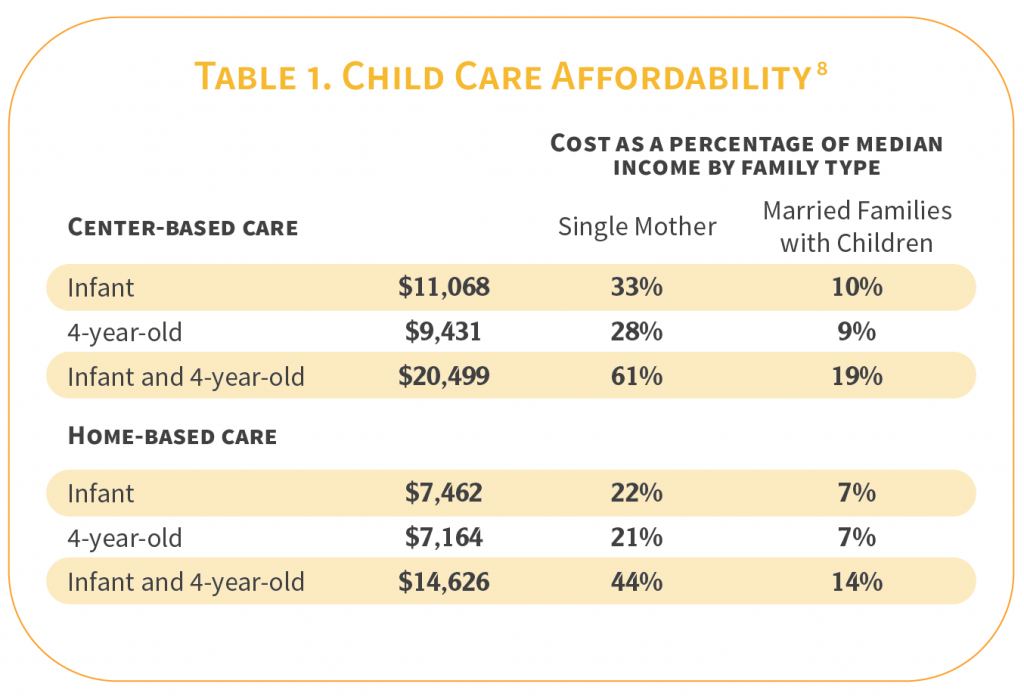

If parents cannot find affordable care, then labor participation becomes harder for them to justify. Based on the most recent data from 2021, however, child care is costing a significant percentage of a working parent’s income. As Table 1 shows, the average rate of center-based care for an infant now absorbs 10% of the median income of a married couple and 33% of the median income of a single mother. Having two young children in need of care becomes especially costly as center-based care for an infant and a 4-year-old absorbs 19% of a married couple’s income and 61% of a single mother’s income.

End Notes

i. Cascio, Elizabeth U. Early childhood education in the United States: What, when, where, who, how, and why. No. w28722. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2021.

ii. U.S. Census Bureau. “Age of Own Children Under 18 Years in Families and Subfamilies by Living Arrangements by Employment Status of Parents.” American Community Survey, ACS 5-Year Estimates Detailed Tables, Table B23008, 2022.

iii. 2020-21 National Survey of Children’s Health, Family Health and Activities.

iv. Shonkoff, J. P., J. Richmond, P. Levitt, S. A. Bunge, J. L. Cameron, G. J. Duncan, and C. A. Nelson III. “From best practices to breakthrough impacts a science-based approach to building a more promising future for young children and families.” Cambirdge, MA: Harvard University, Center on the Developing Child (2016): 747-756.

v. Bishop, Sandra. “Early Childhood Programs’ Scarcity Undermines Nebraska’s Rural Communities: Quality early care and education can bolster public safety, the economy, and national security.” Council For A Strong America Council For A Strong America (2021).

vi. Employed – With a job, not at work, Childcare problems, 2024. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

vii. Based on data obtained from Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services; U.S. Census Bureau, “Age of Own Children Under 18 Years in Families and Subfamilies by Living Arrangements by Employment Status of Parents,” 2022. American Community Survey, ACS 5-Year Estimates Detailed Tables, Table B23008.

viii. Based on Data obtained from Buffett Early Childhood Institute; University of Nebraska at Kearney costs retrieved from www.unk.edu/costs.php; University of Nebraska at Omaha costs retrieved from www.unomaha.edu / undergraduate-admissions/tuition-and-aid/estimated-cost-of-attendance.php; University of Nebraska at Lincoln costs retrieved from admissions.unl.edu/cost/.

ix. For a more comprehensive examination of Nebraska’s child care subsidy and market cost model, we recommend you check out First Five Nebraska’s report written for LR 151 in October 2023, accessible here https://www.first

fivenebraska.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Report_LR151_Cost_Model_FINAL_10.10.23.pdf.

x. Nebraska Revised Statute, Section 77-7203.

xi. Heckman, James J. “Policies to foster human capital.” Research in economics 54, no. 1 (2000): 3-56; Deming,

David J. “Four facts about human capital.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 36, no. 3 (2022): 75-102.

xii. Quarter 4 2023 State occupational Employment and Wage Estimates, 2024. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

xiii. Lowrey, Annie. “Teachers, Nurses, and Child-Care Workers Have Had Enough: The burnout crisis in pink-collar occupations puts everyone’s well-being at risk.” The Atlantic. September 27, 2022. https://www.theatlantic.com/

ideas/archive/2022/09/teachers-nurses-child-care-job-burnout-crisis/671563/.

xiv. Han, Byung-Chul. The burnout society. Stanford University Press, 2015.

xv. First Five Nebraska, Policy Brief LB 1416:bChild Care Capacity Building and Workforce Act,” 2024. https://www. firstfivenebraska.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/LB1416_FFN_PolicyBrief_Final.pdf.

While the high and rising costs of college have garnered much national attention in recent years, a year of child care in Nebraska now rivals, and even surpasses, a years’ worth of tuition and fees at Nebraska’s public universities. As seen in Table 2, tuition and fees at the University of Nebraska at Kearney for the 2023-24 school year was cheaper than the average child care cost of both family and center-based care in 2021, regardless of the age of the child. Even a full year of tuition and fees (2023/24) at the University of Nebraska at Lincoln was cheaper than sending an infant to center-based care in 2021.viii

There are two primary policy mechanics that can be leveraged to impact this cost for working Nebraskan families: subsidies and tax credits.

Subsidies: Our state childcare subsidy is currently offered for low-income families earning up to 185% of the federal poverty level, to help offset costs of approved hours of needed care. Providers can decide whether or not to accept families with subsidies, and if they do, will receive reimbursement based on a child’s attendance during their approved hours of care. These payments are up to the 75th percentile of the market rate for child care, or the rate the provider charges for private pay families, whichever is lower.ix

Tax credits: Tax credits provide another option to help working families offset the costs of care, particularly for those with lower incomes who may qualify for a subsidy but cannot find an accessible provider willing to accept it. In 2023, Nebraska passed the Child Care Tax Credit Act, which goes into effect in 2024 and offers families a refundable credit of up to $2,000 per child enrolled in care. The credit is tiered according to household income, limited to parents or caregivers with household income up to $150,000, and capped at $15 million statewide per fiscal year.x

Quality

With the high-level of economic and social importance of the child care work itself, along with the low-pay and high-level of responsibility placed on the child care workers, it is of little surprise that the workers often suffer from burnout.xiii Burnout is a work phenomenon impacting individuals who are deeply committed to and find the work that they do to be meaningful, beyond the money it earns them.xiv That commitment, however, may lead the worker to overextend themselves to accomplish the organization’s goals and mission – leading eventually to exhaustion and turnover.

This burnout effect is seen in the 30% turnover rate among Nebraska’s child care workers from 2022 to 2023.xv Thus, for our children to have quality care, recruitment, retainment, and appropriate compensation of committed child care workers will need to occur. These efforts must respect the financial, psychological, and emotional well-being of the people who step up to care for our young children.

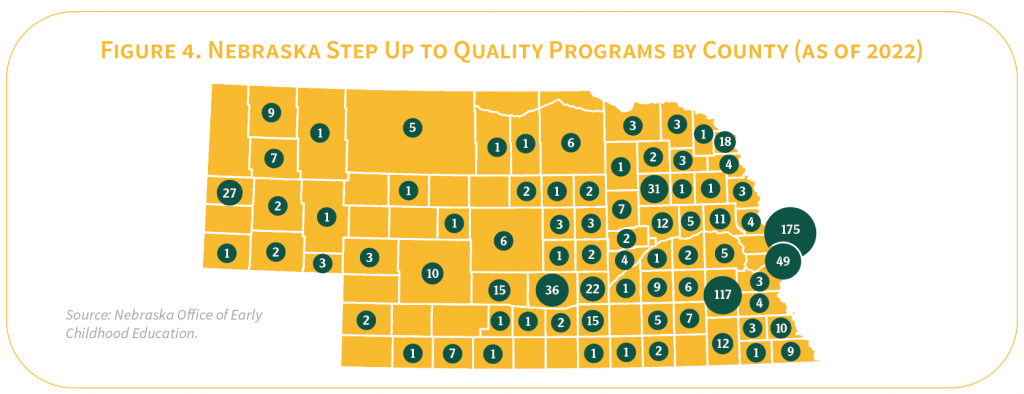

One initiative in Nebraska focused on increasing quality in child care and early childhood education is Step Up to Quality, Nebraska’s quality rating and improvement system for providers. Figure 4 shows a map of “Step Up” rated providers across the state. Participating in Step Up offers guidance, training, and financial incentives to providers to enhance and enrich program quality for the children in their care.