Looking Back After 30 Years of Doing Kids Count in Nebraska

Child Poverty and Family Economic Stability

Too many of Nebraska’s children have experienced and continue to experience economic instability. Nationally, little progress has been made on poverty since the 1970s, with overall percentages fluctuating up and down depending on the state of the economy. The 1993 Kids Count Report in Nebraska Report relied on U.S. Census data from 1990 for poverty numbers, a time when poverty numbers were climbing incrementally, from 12.6% in 1970 to 13.5% in 1990, nationally. Since 1990, overall national poverty rates continued to see-saw, reaching 15.3% in 2010 before decreasing again to 12.8% of Americans in 2021.

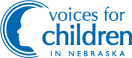

Furthermore, past federal policies decisions–such as leaving domestic and agricultural workers out of social security benefits and the redlining of predominantly Black and Brown neighborhoods–have led people of color to bear a disproportionate brunt of economic marginalization. This can be seen clearly among children in Nebraska. In 1990, as shown in Figure 1 below, poverty rates for children under age 5 in Nebraska varied greatly by race, with 67% of American Indian, 53% of Black, 36% classified Other, 2% of Asian, and 34% of Hispanic origin children classified as poor. Meanwhile, 14% of white children in Nebraska under the age of 5 lived in poverty. More recent data from 2021 shows that 35.8% of Native American, 29.9% of Black, 24.3% of multiracial/other, 22.9% of Hispanic, and 9.2% of white children under the age of 5 are growing up in poverty in Nebraska.³ Although these data show improvements in racial disparities, our systems remain neither economically nor racially equitable. The data could not be clearer: the story of Nebraska child poverty is and has been one of disparities by race and ethnicity.

Implications for Policy Action

As the sociologist Mathew Desmond recently wrote, poverty persists, in part, because of the “unrelenting exploitation” experienced by people at the bottom of the labor market.4 When parents and guardians experience such exploitation, they and their children miss meals, live in inadequate housing, or even go unhoused, struggle to receive needed health services, lack childcare, and miss out on enriching extracurricular activities.

To ensure people’s wages more accurately reflect the value of their work, wages should keep pace with inflation and account for the true cost of living. Nebraskans have now passed two separate ballot initiatives setting a higher minimum wage. Under the most recent scheme supported by voters in 2022, the minimum wage will increase gradually until 2026 and will adjust annually automatically thereafter to account for increases in the cost of living. This investment in working Nebraskans will have positive spillover effects for children, and we should work to ensure the provisions aren’t undermined or don’t evaporate due to price increases on necessities such as rent and food.

But higher wages only count towards those activities officially recognized as work by the labor market. A host of necessary activities, performed by family, friends, and community members alike, typically go unremunerated. We speak here of care work, including but not limited to caring for the young, sick, and elderly. More broadly, this includes the civic work of building and sustaining norms of cooperation and contestation throughout the community. Despite the unpaid or at best low-paid status of such work, these activities serve as the foundation for (1) a strong economy and (2) solving common problems in a democratic society. To make the performance of this work more difficult is to tear at the social fabric holding society together and puts the economy at risk.

For example, at a community meeting about childcare in a rural county this year, staff at Voices for Children heard concerns about the lack of quality, affordable childcare within a four-county area. These concerns were so grave that some feared an entire town would not survive, as residents would be forced to move out to find childcare. Much more work must be done to ensure Nebraskans throughout the state have access to affordable, quality, dependable care. This includes, but is not limited to, ensuring that childcare assistance reaches families who need it, providers are able to receive subsidies at an appropriate market rate, licensing provisions are structured to provide for confidence in the safety of care, and care workers are able to make a living wage.

Child Welfare & Juvenile Justice

Another area of Voices for Children’s data and advocacy work for the past 30 years has been the protection of children and youth in our court systems and out-of-home care. This encompasses what are commonly described as the “child welfare” and “juvenile justice” systems. In child welfare, children who have experienced abuse or neglect come to the state’s attention and may receive a spectrum of services from in-home to removal into foster care in order to ameliorate risk or safety concerns. In juvenile justice, children come to the attention of the state through behaviors that might constitute a crime if committed by an adult, or for other “status” offenses, such as chronic absenteeism from school, which are of concern but not crimes. Many young people “crossover” between child welfare and juvenile justice, both due to increased scrutiny by the legal system and because early traumas in life correlate with subsequent instances of anti-social and risk-taking behaviors.

Our original 1993 Kids Count in Nebraska Report highlighted only one data point for each of these systems: in youth justice, the number of children arrested, and in child welfare, the number of children removed into out-of-home care. Here, we address each of these in turn.

Declines in Child Welfare Removals

In child welfare, since 1974, legislation has often swung between two poles of child protection philosophies: a family-based model that sought to keep children with their biological families whenever possible, and a model that viewed child safety as primarily achievable through the state’s actions in finding a new home.

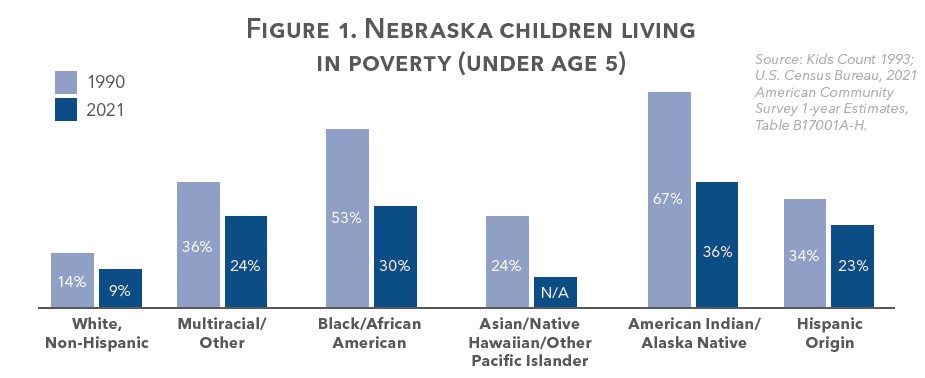

In 1992, 9,525 of Nebraska’s children were separated from their parents and placed in out-of-home care, typically due to child maltreatment cases. Our original 1993 Kids Count in Nebraska Report pointed to these high numbers as an indication of service needs in the state. This is because most child maltreatment cases in the state are due to physical neglect, which is often related to poverty and financial stress. Instead of taking children out of their homes in such cases, in-home services can build parental capacity without disrupting family routines and relationships. In-home services where safety can be maintained also reduce trauma to children, who can experience removal itself as a traumatic event.

Unfortunately, as shown in Figure 2 below, the number of children in out-of-home care only increased over the next 9 years from our original report, reaching a high of 11,518 in 2001. By 2006, there were still nearly 11,000 Nebraska children experiencing out-of-home care in child welfare, but cases began to drop more consistently thereafter. Policy reforms, including the implementation of Alternative Response beginning in 2011 and federal realignment of child welfare funding in the Family First Prevention and Services Act of 2019, continued to allow more flexibility for case workers to better differentiate between cases where a child’s safety is at-risk and cases where supportive services would allow the family to better meet the needs of children. As a result, out-of-home care cases have declined further to 5,199 in 2021. This marks a 45.4% decrease from those originally reported in 1992, and a 54.8% decrease since their high point in 2001.

Over the decades, we have highlighted racial and ethnic disparities and disproportionality reflected in our child welfare system in Kids Count Reports, policy papers, and issue briefs, reflecting multiple and compounding barriers for children of color in Nebraska. Notably, the racial and ethnic disparities in out-of-home cases still tilt heavily toward children of color at radically disproportionate rates. In 2021, among children in out-of-home care, Black children accounted for 18.7%, American Indian/Alaska Native children for 6.5%, multiracial children for 9.0%, and children of Hispanic origin accounted 22.4%. Overall removals may have decreased over the past decade, but significant overrepresentation of children of color in foster care remains, particularly Black children and American Indian children.

Declining Arrest Rates of Children and Youth:

At the end of the 20th century, when our we began publishing Kids Count in Nebraska Reports, Nebraska was part of the national prison construction trend. Broken windows policing, stop-and-frisk strategies, and fears of so-called super predators led to growing confinement of both adults and children.

As highlighted in our original 1993 Kids Count in Nebraska Report, the number of children arrested rose from 13,401 children in 1988 to 15,991 in 1992. Subsequent Kids Count Reports continued to track arrest rates, showing the number of arrests eventually rising to 21,377 in 1998, a 59.5% increase since 1988. Thus, in 1998, the arrest rate per 1,000 youths in Nebraska stood at 49.8. In the subsequent decades, the super-predator scare was thoroughly debunked, and a growing understanding of adolescent development contributed to better approaches to holding young people accountable for their actions. Although it took until 2011 for youth arrests to fall below those in 1988, incremental declines were happening and continued until, as this year’s report shows, youth arrests in Nebraska were down to just 4,932 in 2021. As such, the arrest rate per 1,000 youth stood at 10.2 in 2021, good for a 79.5% decline since arrests peaked in 1998.

Yet again we see overrepresentation when we disaggregate arrest numbers by race and ethnicity. Though we do not have race and ethnicity breakdowns for the 1990s data our original report, by 2021, despite making up only 6.0% of the total population, Black youths in Nebraska accounted for 15.3% of youth arrests and American Indian/Native Alaskan’s accounted for 3.2% of youth arrests, but only 1.1% of Nebraska’s youth population. Meanwhile, youths of Hispanic origin were 18.9% of the youth population and accounted for 22.0% of youth arrests.5

Implications for Policy Action

Though child welfare and juvenile justice are formally separate systems, children and families frequently experience crossover between them, and underlying causes of involvement – and modes of intervention – are often intersectional. Communities in poverty and communities that are subject to structural racism are frequently the same communities which are overpoliced and overrepresented in these systems. The progress of both child welfare and juvenile justice policy over the decades has been underpinned by growing understandings of the importance of primary prevention and upstream investment at the local level to build community wealth and support families in meeting their children’s needs. Systems which were initially built on “safety”– removing children from their families and neighborhoods – must continue to evolve to access community strengths and support familial resilience.

To Voices for Children, that means:

• Explicitly identifying systemic racism giving rise to disparate outcomes and acknowledging our own failure, as an organization, in addressing the harms which continue to be perpetuated for children of color within these systems;

• Increasing investments in primary prevention programs like food stamps, rental assistance, childcare subsidies, and Aid to Dependent Children cash assistance, and more broadly in historically underfunded communities and census tracts;

• Reevaluating mechanisms for reporting maltreatment and training reporters in bias and distinguishing poverty from true neglect;

• Providing meaningful supports for formal and informal relative and kinship caregivers, who step up to provide loving, trusted care for children when a removal must occur for safety;

• Building out our system of care and supporting mental health points of contact in schools, to address rising mental health needs among children and teens;

• Continuing to reduce our numbers of youth incarcerated and removed from home, reinvesting that money in wrap-around supports in the home and neighborhood; and

• Pressing forward toward restorative justice approaches which center around community and place addressing harm at the core of justice.

Concluding Thoughts

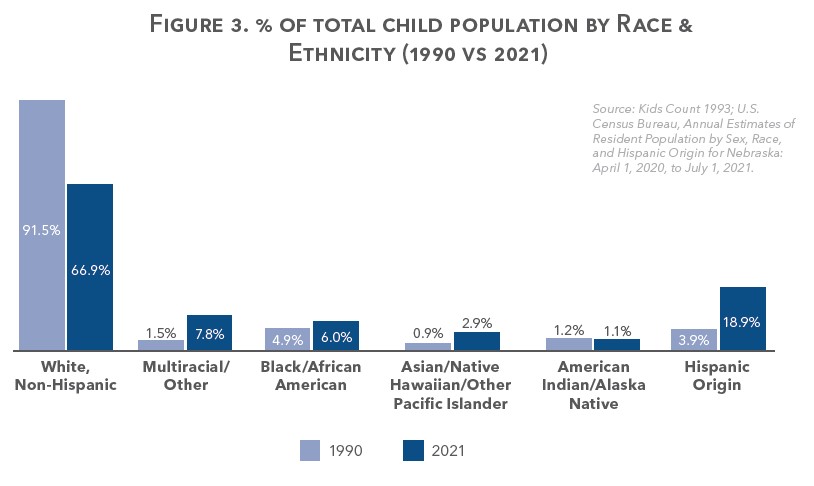

In our original 1993 Kids Count in Nebraska Report, we highlighted demographic population data and have noted shifts ever since. As Figure 3 above shows, from 1990 to 2021, the percentage of Nebraska’s children (age 17 and under) who were white declined from 91.5% to 66.9%, while the percentage of Native American children remained relatively steady—from 1.2% to 1.1%. Meanwhile, the percentage of Black children rose from 4.9% to 6.0%; the Asian/Pacific Islander child population rose from 0.9% to 2.9%; and the multiracial/other child population rose from 1.5% to 7.8%. Finally, the Hispanic origin child population rose from 3.9% in 1990 to 18.9% in 2021. While our systems should be racially equitable regardless of how large or small certain populations are, the growing diversity of Nebraska’s youth only increases the urgency for reforming and remaking legal, economic, education, and health systems to work fairly for all children.

With 30 years’ hindsight, the Beanie Babies craze did not stand the test of time. Ensuring Nebraska stands the test of time will require strong communities, where every child – regardless of race or ethnicity – has all they need to lead a healthy, secure, fulfilling life. This is the Nebraska we hope to see when, in the year 2053, we publish our 60th Kids Count in Nebraska Report. We will continue to work toward that vision and be documenting and sharing the data as we go.

End Notes

1. Bissonnette, Zac. “Excerpt From The Great Beanie Baby Bubble.” Penguinrandomhouse.Ca. Accessed February 13, 2023. https://www.penguinrandomhouse.ca/books/313121/the greatbeanie-baby-bubble-by-zac-bissonnette/9781591848004/excerpt.

2. “Foster social equity”. NAPAwash, https://napawash.org/grand-challenges/foster-social-equity.

Accessed 7 March 2023.

3. U.S. Census Bureau, 1990; U.S Census Bureau, 2021 American Community Survey 1-year Estimates, Tables B17001A-I.

4. Desmond, Matthew. “Why Poverty Persists in America.” New York Times Magazine, 9 March2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/09/magazine/poverty-by-america-matthew desmond.html.

5. Kids Count in Nebraska Reports began disaggregating arrest data in 2007. Nebraska’s Crime Commission disaggregates race and ethnicity categories different than many other agencies. Most notably, the Crime Commission does not provide a multiracial category and does not distinguish between white, non-Hispanic origin and white, Hispanic origin.